Climate science exploded into the political hemisphere on 23rd June 1988 and seemed to require huge government intervention in the markets. So how would the free market politicians react? In the next three posts we see how Margaret Thatcher responds to James Hansen’s call to action…

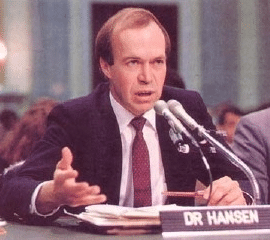

The mercury reached 98 degrees in Washington, DC on Thursday 23rd June 1988, and pearls of sweat could be seen on professor James Hansen’s furrowed brow as he stood to give evidence before the United States Senate Committee on energy and natural resources.

“The present temperature is the highest in the period of record,” he murmured. “The rate of warming in the last 25 years” he said pointing at a chart, “as you can see on the right, is the highest on record.”

The NASA scientist read nervously from his prepared statement, titled The Greenhouse Effect: Impacts on Current Global Temperature and Regional Heat Waves. “In my opinion, the greenhouse effect has been detected, and it is changing our climate now.”

These softly spoken remarks made front page news across the United States within hours and reverberated around the world. The evidence that climate change was already taking place appeared everywhere: the Amazon rainforest in Brazil had been devastated by raging fires; crops in the Midwest of the United States had been scorched; and farmland across the country had been ablaze.

Michael Oppenheimer, a campaign veteran at the Environmental Defence Fund, said at the time: “I’ve never seen an environmental issue mature so quickly, shifting from science to the policy realm almost overnight.”

Political agenda

Hansen’s testimony appears to have inspired immediate government action, and for a brief moment public policy reflected the best science of the time. Before the end of the year, more than 30 bills relating to climate change had been introduced to the United States Congress.

Robert Darwall, author of The Age of Global Warming: A History, states: “Global warming’s entrance into politics can be dated with precision—1988: the year of the Toronto conference on climate change, Margaret Thatcher’s address to the Royal Society, NASA scientist James Hansen’s appearance at a congressional committee, and the establishment of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.”

HOW CLIMATE SCIENCE BECAME A POLITICAL ISSUE

Part 1: James Hansen: How Climate Change Became Political

Part 2: James Hansen: I Thought There Would Be a Rational Response

Part 3: How Free Market Thatcher First Called for Climate Action

Next Week: Monckton’s Odd Claim He Inspired Thatcher’s Climate Call

Hansen would in turn be lionised and reviled for placing the science of climate change so firmly on the political agenda. Mark Bowen, in his book Censoring Science, described him as being “almost universally regarded as the permanent climate scientist of our time”.

He would be accused by climate sceptics of initiating a global scam where reputable researchers would suddenly hype their findings and exaggerate the risk to the human race to gain access to billions in government grants and increase their funding.

Hansen, by this reckoning, was a showman of incredible cunning, capable of staging the most audacious hoax in front of the Senate—the most highly educated and specialised community in the world—and the world’s media. If Hansen is a fraud, then he is certainly the most accomplished in human history.

Ascetic life

When he appeared before the Senate, he owned a small farm in rural Pennsylvania. The back seats and floor of his rusting Volvo were often covered with straw.

He lived an “ascetic life” in a modest apartment a few blocks from his cramped office at the Goddard Institute of Space Studies and would wake up at 4.30am on many days to attend meetings at NASA headquarters. He was middle America.

His father was an itinerant tenant farmer who, after leaving school aged eight, would marry, settle down as a bartender and have seven hungry children. “We would move from one farm to another, giving half of the crop to the owner of the farm and getting the rest ourselves,” Hansen would recall of his childhood. “And that was a socially useful function.”

As a boy, Hansen was exceptionally good at maths and won a scholarship to study physics at the local university. It was the American dream: a desperately poor child of brilliant intelligence who worked hard at school, was discovered and nurtured.

It was by chance that he would meet professor James Van Allen who was busy building instruments for the first American satellite to be sent into space. “I was so shy and unconfident that I avoided picking any classes under professor Van Allen; I didn’t want him to know how ignorant I was,” Hansen recalls.

Venus in furs

He graduated in 1963 with the highest distinction at the university, and in doing so came to Allen’s attention. The professor persuaded him to study Venus for his PhD. “It turned out that the reason Venus was so hot was because it has this very thick carbon dioxide atmosphere.”

The physicist completed the NASA graduate programme and was soon made principal investigator on the Pioneer Venus Orbiter project where he dedicated five years of his life to designing and building instruments that would examine the clouds of Venus.

His stellar rise did not result in increased self-confidence. “My brain seemed to freeze up before an audience,” he would admit in his autobiography. “Once, at a Pioneer Venus mission meeting in the 1970s, when I went to show a viewgraph, I could not think, so I just went back to my seat—which was very embarrassing.”

Shortly before the completion of his Venus mission, a Harvard postdoctoral researcher approached Hansen for advice. The short meeting would change his life, and it should have been the moment that we discovered fossil fuels posed a risk to life itself.

The researcher was interested in how the greenhouse effect—which made Venus uninhabitable—may be affecting the temperature of the Earth’s atmosphere. “I decided that this planet was actually more interesting than Venus,” Hansen remembers.

“This is a planet where people and many other species live; it’s more interesting and important to understand this planet.” He abandoned his life’s work and resigned from the Venus experiment.

The space probe went ahead in May 1978 without him and discovered that carbon dioxide-driven climate change had resulted in the atmosphere on Venus being soaked in sulphuric acid. He used his expertise in early computer modelling to begin analysing the effect of increased carbon dioxide and methane in the Earth’s atmosphere.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts